Perfect Circles: Sharp Precision Wheels

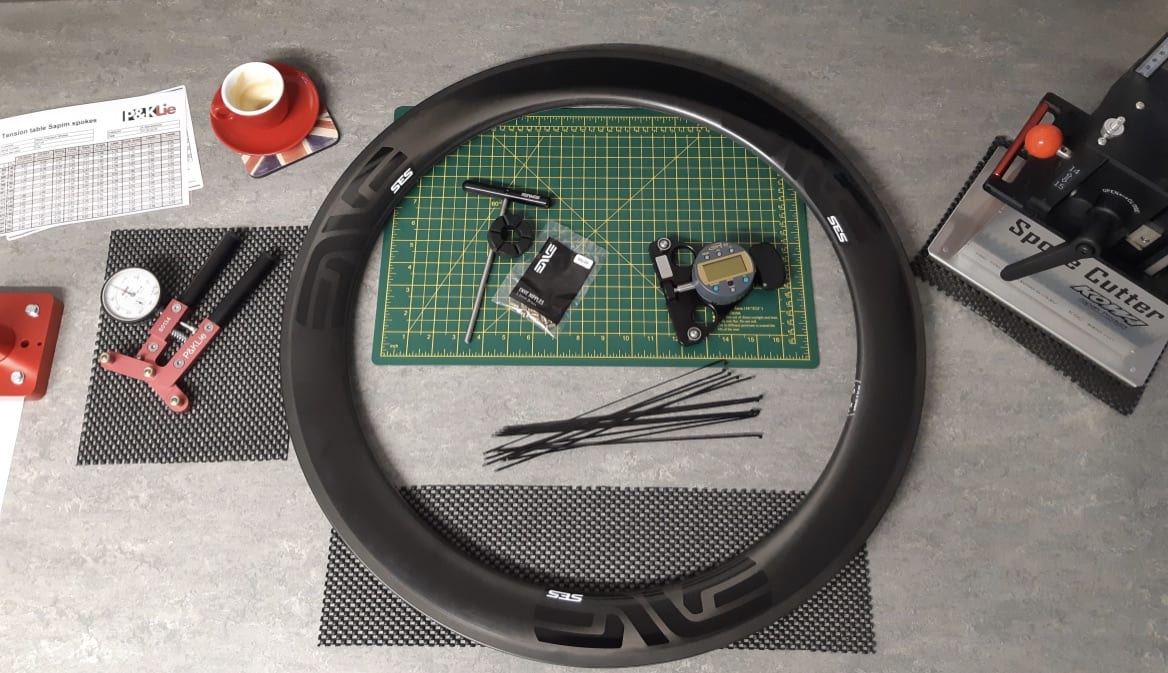

jim cotton Interest England 05 December 2018

You log into Wiggle. Press a few buttons, read a few specs, idly cast your eye over a few reviews, press a few more buttons.

Before you know it, the Wiggle workforce are picking and packing a set of £800 wheels into a box with your name on it. It’s all too easy.

Cycling Journalist and blogger Jim Cotton visited Sharp Precision Wheel’s workshop in the U.K where he met Founder Ben Sharp to discover the intricacies of custom wheel building.

Wheelsets, like most things in cycling, and in life in general, are becoming another commodity that we buy and sell without really thinking about it.

But, away from the huge factories of Mavic, Zipp and Fulcrum, artisans are creating wheels specifically specced to match a rider’s needs, spending hours painstakingly crafting wheels built to fulfil the dreams and demands of their customer.

Master wheel-builder Ben Sharp of Sharp Precision Wheels recently invited me to his workshop to find out more about the fine art of wheel building, and it’s totally changed the way I look at those hoops beneath my frame.

When is a winter wheel not a winter wheel?

Ben and I start the day by talking about my current winter wheelset. Like many, I chose these training wheels from a large website, spending a few hours finding the balance of price, marketed performance, and the throwaway opinions in reviews. Many of us, myself included, fall into the trap with winter wheels of just buying any old wheel that’s cheap, but still relatively fast and lightweight. Our egos and need to keep some sense of respectability on Strava just don’t allow us to buy a heavy yet practical set of wheels. My winter wheels are simply cheap race wheels – not winter training wheels.

When I purchased the wheels, several years ago, considerations essential to the way in which the items would be used – during endless hours of base training in the muck, grit and cold of the grey UK roads – were given only a moment’s thought. How serviceable are the hubs, when they’ve been rotted away by mud and grime? Can you easily pop a tyre on and off them with freezing cold hands? Are they strong enough to tolerate the appalling states of the roads in Oxfordshire and Berkshire, battered by the freeze and thaw of winter?

With a wheel-builder, those considerations would have been forefront. Ben specs my ‘correct’ winter wheels without hesitation. I needed something with a relatively low spoke count – probably 28 – to match my low weight – laced in a traditional two-cross pattern as it’s strong. I needed brass spoke nipples as they’re cheap, but resistant to corrosion. And the rim should be relatively cheap as the brake tracks will wear fast in the mucky conditions – a rim isn’t something that can be serviced, but that can be replaced easily. I’m told I need a DT Swiss R460 rim – one that balances price, performance and, vitally, ease of tyre installation. Ben advises that the hub deserves a little more investment; something that could be serviced as often as the conditions dictate, such as a DT Swiss 350. Buy a cheap hub, and you’re looking at a wheel you’ll end up having to throw away as it’s not economically serviceable. And Ben doesn’t build items you put in the bin.

Do Mavic, Fulcrum, Shimano or any of the big manufacturers make a factory wheel specifically designed for light riders looking to do a lot of winter miles on poor roads? And do they produce this exactly for my budget? No. And what’s the chance they’ll give you a cheap wheel with a hub that can be easily serviced? Minimal. More than likely I will be sold a proprietary spoke and lacing pattern which is hard to replace parts on, and troublesome if the worst should happen, miles from home. Do the big brands want to sell you a wheel that will last for years and years? Only if they want to do themselves out of business.

Sure, when I purchased my winter wheels I didn’t need to spend time consulting a craftsman or pay extra for their labour. I did however spend time reading reviews and marketing blurbs, then putting blind faith in what I had read.

Speaking with Ben makes it totally apparent how consulting a wheel-builder provides clarity and confidence in your investment. It’s like speaking to a real person on a helpline rather than going through the dispiriting process of working through an automated system, saying random words to a robot as you work through a tree of options. Speak to an expert and you get expert advice, matched to your needs.

And that process of consultation makes you consider more thoroughly your needs as a rider. All those years ago, I don’t recall really considering what I really needed from a wheel set. Did I want resilience, comfort and serviceability, or something cheap but ‘fast’ to flatter my Strava profile? Speaking with Ben has made me re-appraise my choice. Those winter wheels on my mucky bike in the hallway are in no way training wheels. They’re just A.N. Other set of wheels that I saw cheap.

OK, so if I’d gone hand-built all those years ago, I may have paid a little extra: bespoke service don’t come free. However, spending time with Ben in his pristine workshop shows that the minimal labour charges these craftsmen ask for renders hand-built wheels as close to a steal as you can get.

Labours of love

I spent the day watching Ben building a radial front wheel, and the level of care, effort, and attention he invests is evident. Not just the focus as he starts tensioning the wheel on his exquisite truing stand – a machine that looks a piece of art in itself – but the physical work he invests in de-stressing the wheel. De-stressing is a strenuous process of applying force to the rim as the wheel is being tensioned, an act that effectively embeds the wheel into itself, meaning a greater level of tolerance and thus longevity can be worked into the build. He does this over and over again, using his hands and bodyweight to stress the spokes and rim, something that leaves imprints on his palms and a fit young man short of breath. This process is automated and less frequent in a factory.

By using his hands to de-stress an evolving build, Ben is able to feel and experience the wheel in action, sort of a proxy for riding the wheel. Feeling how the progressing wheel reacts in his palms allows Ben to determine the ride-feel of the wheel, like how a master baker can assess how a dough will prove and rise as he kneads it.

“As I work through the build, I gain an understanding of how the materials in my hands are interacting and performing together. It gives me a feel for the characteristics of the finished wheel. It can be an immersive, almost obsessive experience.”

Building a wheel isn’t like sitting typing emails – it’s a hands-on, experiential process, and something I’d not really appreciated before watching him at work.

The mental and physical focus I can see Ben paying to the tensioning and de-stressing of the wheel really proves to me that when you get those hoops back from the workshop, you get a set of wheels that someone has spent maybe eight hours of their life creating just for you. For that day of their life, they were devoted to doing their utmost to build something that will make you very, very happy.

A wheel from a factory is merely another serial number, not the labour of love of a hand-built. The small additional price you pay for that service really is almost embarrassingly low – a sign of both how we’ve lost appreciation for true tradesmen’s work, and how big businesses can squash these small guys into the floor with their big volumes and low margins. Watching Ben work and understanding his processes give me a feel for how investing in a hand-built wheel is like a return to the world of buying your fruit and veg from the grocer, your meat from the butcher, and baking your own bread when the bakery has already run out of your favourite seeded batch. A time when produce was painstakingly grown, developed and laboured over, and was evident in the vibrancy of what ended up on your plate.

When Ben left Strada, he didn’t do it in a bid to build an empire and make millions. Let’s face it, setting up your own wheel-building business in the quiet town of Billingshurst, South England, isn’t a move you make when you want quick cash and early retirement. His motives are clear – sharing his skill and devotion with riders, and forging his own passion for riding into every wheel.

“If I lost the sense of love and care for the wheels and for the rider’s best interest, it wouldn’t be worth it.”

Ben isn’t just a builder, but a rider in his own right – like me, he’s a mountain goat and Marmotte addict, and he clearly wants to infuse his love of riding into all his wheels. Get a wheel from Ben and you get a wheel that he wants to last, and that he wants you to love. Having instilled his own devotion to the craft in building a wheel, he wants to pass it on to you. A Sharp Precision Wheel is built to be serviced, and Ben wants you to be able to service the component yourself. And for the nervous and clumsy, such as me, he would choose a simple hub that requires the minimum tools to work on – all a part of the beauty of consulting an expert and creating a wheel from hand-picked components, rather than buying off-the-shelf. With even the simplest of hubs, Sharp Precision wheelsets come with a beautifully crafted user-manual that details how to care for the wheels and guides you about how to service them. The booklet isn’t a throwaway gesture, but a statement of intent; you’ve got no excuse for letting the wheel deteriorate. The wheels were built with love, and Ben wants you to show appreciation for the materials and the build process by looking after them – to the point that he provides all his customers with a small pot of grease for maintaining the freehub.

“It’s a simple gesture but it helps people to understand the needs of their wheels and take care of their own product. I want people to take pride in their hand-built wheels and one of the best ways to do that is to show them how to properly care for them.”

With his top end builds using ENVE rims, Ben’s appreciation for the quality of the components, his desire for you to experience them at their very best, becomes even more evident. These dream wheels are sold with a free future service, with Ben covering the collection and delivery charges as well as his labour cost. As we look over one of the ENVE 3.4 rims in Ben’s well-stocked stores, the way Ben holds it and points out its features betrays the admiration he has for it; it’s not just a component but a work of art and craft. A hand-built carbon rim such as this clearly resonates with him; it’s been through a process similar to that which his wheels go through – hours of human labour and attention – and he clearly connects with it at a level that I cannot appreciate. This deep understanding for, and appreciation of, what to me is just a sexy looking piece of carbon shines through in Ben’s promise to help customers look after them in the future. He’s willing to invest his time in an item of such quality as the component deserves it – and so you deserve the best experience with it.

Experiences, not eggs-periences

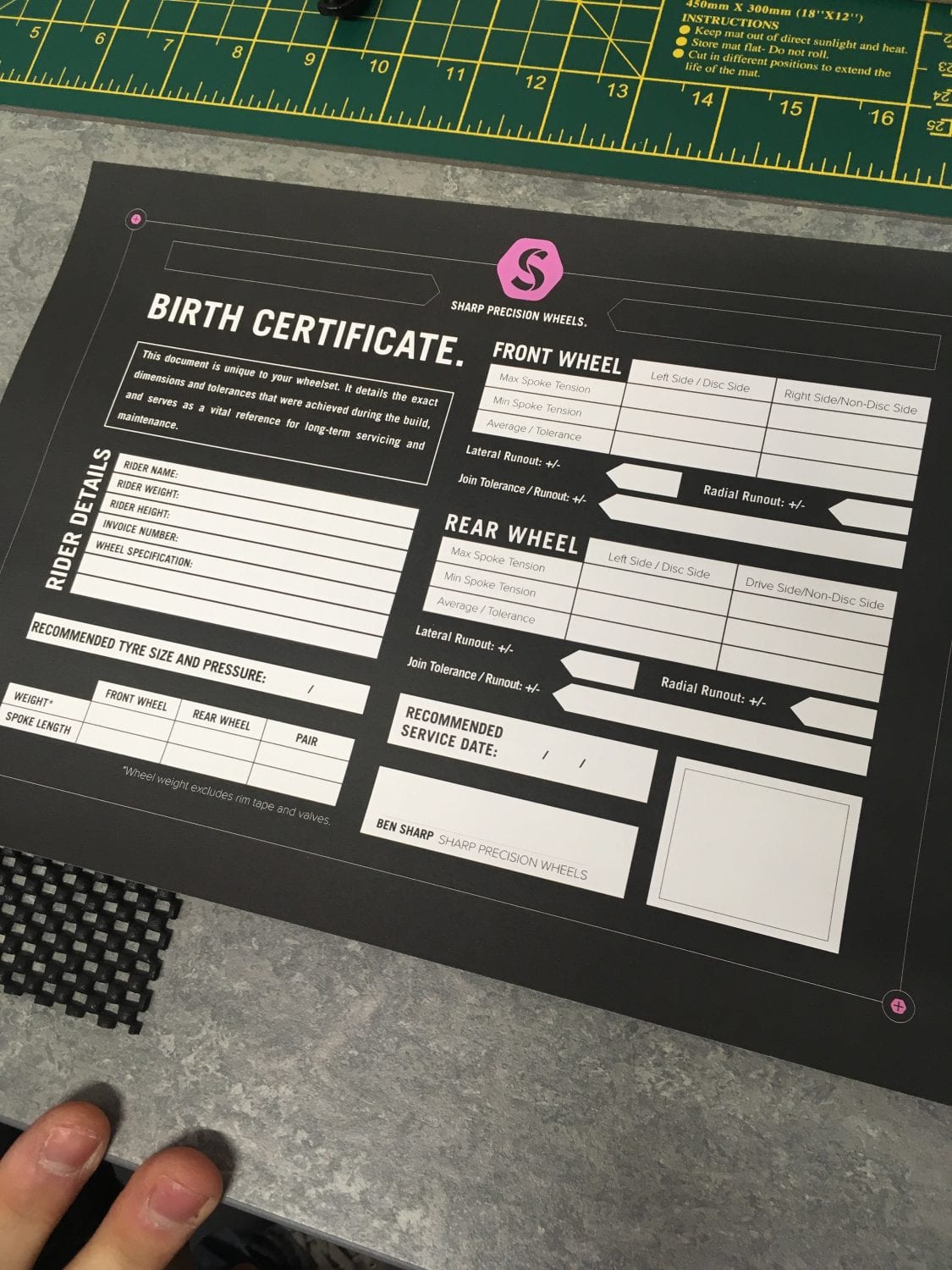

The instruction manual that Ben provides with his wheels is just the start of the things he does to provide you a proper experience and sense of a crafted product rather than a machined item. The instruction manual is hand-signed, there’s a custom decal with Ben’s branding on the hub, and the wheels come with a ‘Birth Certificate’. What Ben produces are his own babies, and he treats them as such. For Ben, these finishing touches are provided with the intent that peoplewill be “reminded that their purchase was really important to me, and my effort focussed on them personally.”

The Birth Certificate doesn’t only provide information for the user about optimal tyre sizes and choices, but proof of Ben’s labour – the exact tension in the spokes, and the ‘runout’ of the wheel – runout basically meaning how circular the wheel is, and how true it is as it turns. For your average joe, the runout information is meaningless; a nice to have. However, it’s like a hand-written roasting date on some coffee beans from your local roaster, or some soil on your carrots from the local market; it’s a sign of authenticity and the human process behind the product. And, for Ben, it helps with after-service. Having notes on the wheel’s history means he can work on it more easily if it needs re-truing or complex servicing. Hand built wheels are not throwaway wheels.

The instruction manual, birth certificate, decals and branded delivery boxes from Sharp Precision Wheels show that for Ben, a pair of hand-built wheels, like cycling itself, is about experience. Ben wants the whole process of speccing, buying, and riding a new component to return us to a side of cycling that we can lose touch with.

When we were children, we rode bikes on stabilisers round and around in circles, delighting in the new-found excitement and exhilaration of what this machine could do for us. Now, for many of us, cycling is Strava segments, PRs and watts per kilo. The love and feel of the machine has become a little clouded.

And this desire to reconnect riders with the basic joy of riding seems to be on the rise throughout the cycling community. Gravel riding, bikepacking, titanium frames and framebags are the new ‘thing’ – even though they’ve been around longer than electronic gears, carbon frames and bike computers. Hip kids in the peloton EF Pro Cycling are now partnered by Rapha and will be sending their thoroughbred racers to take part in all manner of events from fixed gear crits to endurance MTB races so that they can ‘connect the sport more meaningfully to a modern audience’. There seems to be a yearning throughout the cycling world for a little more authenticity, a little more ‘love’.

Maybe, next time you’re staring at a wattage number on your bike computer in the dying minute of your next interval session, think about how it all started and why you ride. How connected to the bike do you feel? I’ve not ridden a pair of hand-built wheels, but I know many who do, and I feel like I’m missing a trick. There’s a slight element of humanity missing in my riding, a few too many stats and not enough connection with my bikes. Whilst I love the numbers and suffering of training, there’s room for me to get my endorphins from the experience of the bike on the road, as well as the satisfaction of burying and improving myself. Maybe a pair of hand-built wheels is the first step.

Having spent time with Ben, I get the sense that there’s factory wheels and there’s hand-built wheels, and then there’s hand-built wheels and Sharp Precision wheels.

One thing that resonated with me when I spoke with Ben is that his building process – the time invested, the tools used, the expertise invested – creates a wheel that can be rounder than a factory wheel, or than that produced by less-practiced builders. I never really considered the possibility of wheels being slightly egg-shaped. For me, all wheels were circles, and that’s as far as I thought about it. But now I know better, and I know that not all wheels are created equal. The idea of riding an oval set of wheels that was hardly touched by a human throughout the build makes me a little uneasy.

I know where I’ll be going when the time comes to invest in some artisanally-produced perfect circles.

-

Jim Cotton, Journalist and Freelance Writer

Visit site -

Sharp Precision Wheels

Visit site